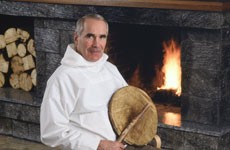

Interview with Pentti Kronqvist, the fireman who founded Nanoq Arctic Museum

I recently returned home from the Mexican Caribbean where I lived for about seven months. I used to sit in an almost glowing heat by the seashore and watch the turquoise waves hit the marvelously white coral sand and the figurative rock formations of Isla Mujeres. Now I’m watching images of arctic sunrises and inland ice, of weather-beaten hunters from Greenland shooting and cutting up walruses and narwhals. From the way, I saw it, their options were pretty limited when it came to hunting. I have come to interview Pentti Kronqvist, founder of Nanoq Museum.

Nanoq Museum is located in the forest area called Fäboda outside Jakobstad, a little town on the west coast of Finland. I grew up in this town, as did Pentti who was born in 1938. Or more accurately speaking, he spent his childhood in the beautiful Fäboda forests right by the sea and explains that his love for nature was eventually one factor that led him to his travels to the Arctic.

“I’ve always been interested in nature. I grew up here by the sea and used to do a lot of cross-country skiing during winter. In 1966 I skied over the ice to Umeå in Sweden. I was also attracted by the Lappmark area[1] and used to ski there a lot in the 1950’s. That is, I used to make skiing trips from village to village – this was before the times of downhill skiing and modern ski lifts.”

Pentti worked as a fireman specialized in diving in those days. The very same year he headed towards Sweden over the Bothnic Gulf, the legendary traveler Christer Boucht was part of the first Finnish expedition to Greenland, led by Erik Pihkala. Five years later, in 1971, a new expedition to Western Greenland was under preparation. The group consisted of Pihkala together with Boucht and his son Peter. They needed a fourth man and this was how the arctic adventures of Pentti started.

“One Sunday afternoon Christer came to the fire station where I worked. I knew of course who he was. He had been asking around for suitable persons to go to Greenland and apparently a lot of people had recommended me. I was a rescue diver and had professional first-aid skills, which was of course very useful. So he asked me if I wanted to Greenland and it was an offer I couldn’t refuse – anyone would have been honoured by such an offer.”

The first trip lasted for a couple of weeks under which the group made a 200km trip from the southwestern coast of Greenland to the inland ice and back. According to Pentti this was more of a hiking trip and they were not faced with greater difficulties. But there were more obstacles to come on later expeditions. In 1976 Pentti set out to make a trip from Northern Greenland to Canada. The group started off from the US Air Base in Thule and were later accompanied by the local Inuit Avataq Kernaq och Akumalik Kunanapik who were planning to hunt ice bears. Due to altered ice conditions they had to make an unexpected roundtrip to be able to cross over to the Canadian side, which eventually made the trip about 800 km long instead of the planned 400-500 km. Pentti had also injured his leg earlier on the trip which made it no easier. He sums it up in a matter-of-fact voice: “We were about to freeze to death. I thought ‘never again’”. The following year, however, Pentti was off again to Thule, the northwestern district of Greenland.

Pentti says he has a special interest for the Arctic people and their traditions. Apart from being an admirer of nature he expresses great respect for the Arctic people’s skills and knowledge of surviving in a harsh environment. Or perhaps ‘surviving’ is not even the correct word – for according to Pentti they truly live in harmony with nature, taking no more from it than they need. Anecdotally he tells how the French actress Brigitte Bardot ran a campaign against seal hunting in the 1970’s, wondering why the Thule people were hunting baby seals. “The Inuit would never do that”, Pentti says. “Baby seals are for them like money in the bank is for us – they wait until they grow older and then hunt according to their needs. Baby seals were in fact slaughtered by Canadian and Norwegian hunters who needed them for making nice-looking furs for the fine ladies [of the industrialized world]”.

The Inuit of Greenland have of course undergone vast changes during the last century. Modern weapons and materials were introduced to them in the beginning of the 20th century, during the time which Christianity was also brought to Greenland. Like in the case of several other colonized peoples in the world, they were subjected to foreign-brought deceases and they adopted new consumption behaviours, such as the use of alcohol which has had devastating and rather well-documented effects. On the other hand, the Inuit were never reduced to mere objects of exploration or data mines for outside research. In fact, many of the ‘conquests’ as we know them wouldn’t have been possible without their help in the first place. In his book Inuit Pentti writes about the well-known US explorer Robert Peary who was the first man to make it to the North Pole in 1909. Peary was the leader of the expedition, but what is often forgotten is that he was accompanied by four Polar Eskimos[2] and part-Inuit Matthew Henson. The latter died poor and unknown in New York in 1955 and the rest of the group was largely forgotten as well, despite the fact that Peary himself mentioned them in several of his own accounts (Kronqvist 1988, 94; see also Kronholm 1997, 57.).

The story of the courageous white man conquering the world is rather familiar. Reading Pentti’s book I suddenly come to think of a lecture I attended years ago at the Helsinki University. The lecturer and accredited scholar Anja Nygren told about her research on travel accounts from tropical America published in the National Geographic during the years 1888-2004. In the article based on this research Nygren concludes that the late 19th and early 20th century writers “present heroic stories of solitary explorers who survey hitherto unknown rivers and hack their way through tangled forests, carrying heavy packs of supplies and enduring the pervasive isolation of the jungle” (Nygren 2006: 508). It is perhaps not surprising that a similar logic applies for the polar region. Pentti claims in his book that “[t]he Great Expeditions in the polar region have always been attributed to the white man“. As for the forgotten investment of Peary’s expedition crew he makes a rather bleak comment: “Ingratitude is the way of the world” (Kronqvist 1988, 94.).

One of the main ideas of the museum was then to share knowledge about the polar people’s history, traditions and their part of the stories of conquest and exploration. The museum was opened in 1991 and got its name from the Greenlandic word “nanoq”, meaning ice bear. It has since been awarded with several national and international prizes, such as the Leonardo da Vinci Medal for the special exhibition of the Italia expedition in 1933.

The museum building and its surrounding cottages are in themselves a tribute in kind to a way of life in harmony with the environment. That is in fact how it all started. Pentti used to collect old timber and wood material to build small cottages in the forests of Fäboda. What other people would have thrown away he collected and made into a cottage, then another and yet another, until he had constructed a little village now known as “The Bear’s Lair” in the midst of the forest. Later on his travels to the Arctic he collected various artefacts as simple memories. In time the collection grew bigger and bigger and he finally decided to set up a museum.

“Lennart Koskinen, priest and now retired bishop of Gothland, once asked me over a cup of coffee: ‘Why did you build this museum?’. I said to him: ‘What would I do with all these things I’ve collected? Better share all this knowledge and information with the coming generations. You know, we do not take anything with us when we die’. And then he [Koskinen] understood me, he said: ‘Yes, you are right, we do not take anything with us. When we go, the very last thing is taken from us.”

I am now back in Helsinki where I currently live. I am thinking about the majestic flashes of light that lit up the Caribbean horizon during the hurricane season in October. I am also thinking about northern lights painting the arctic skies and illuminating the tips of ice bergs looming peacefully in the dark waters – I am wondering how distant these images are form each other and how at the same time they connect me to similar kinds of thoughts and feelings. We are all on the same planet, we all make use of our surrounding environments in different ways. I am thinking about how Pentti used to be fascinated about the old hunters’ stories, because it was in them he could hear echoes of the indigenous way of life that has now undergone permanent changes. I am wondering whether he really crossed that many cultural borders when he traveled to the Arctic – building his cottages in Fäboda he built a peaceful relationship to the nature around him, and it was the same peaceful dwelling he later found in the polar region.

Notes: [1] ‘Lappmarken’ is a Swedish term used since medieval times to denote the area inhabited by the Sami people. In English this region is commonly referred to as Lapland.

[2] The words ’Eskimo’ and ’Inuit’ are used interchangeably by Pentti Kronqvist. ‘Inuit’ is the Greenlandic plural word for “human” and ‘Eskimo’ means “raw eating”, derived from some Arctic peoples who eat meat raw instead of drying it. Although ‘Eskimo’ has some negative connotations both for some Inuit and for people in general, Pentti points out that there are Inuit who call themselves ‘Eskimos’.

Sources:

Kronholm, J. (1997). Nanoq – ett arktiskt äventyr – arktinen seikkailu. Föreningen Nanuk.

Kronqvist, P. (1988). Inuit. Jakobstads tryckeri och Tidnings Ab.

Nygren, A. (2006). Representations of Tropical Rainforests and Tropical Forest-Dwellers in Travel Accounts of National Geographic. Environmental Values 15, no.4: 505–25.

Interview with Pentti Kronqvist 29.05.2015

Katarina (FI) is a creative violinist with an MA in political science. #dance #helsinki #på_svenska